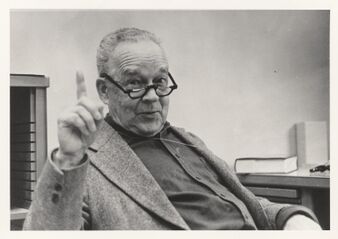

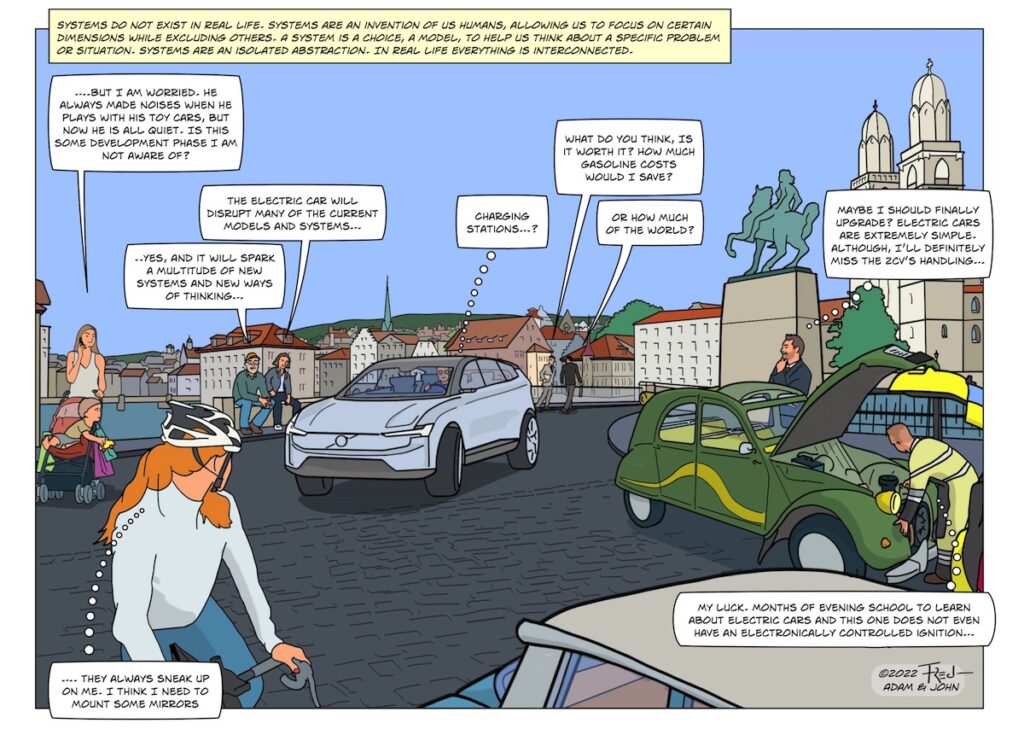

A System is a way of looking at the world.

What is a system? I like Gerald Weinberg’s (1975) answer to this question, that “a system is a way of looking at the world.” This emphasizes that a system is analogous to a piece of art – it is a representation or model that an observer creates. It emphasizes that the system is not an ‘objective’ thing that exists independent of the observer. Rather, a system is a representation. As a representation it will make some things about the phenomenon being represented salient, and it will hide other things. I’ve long understood this position intellectually – but it has taken me much longer to appreciate the deeper meaning and the practical implications of this definition.

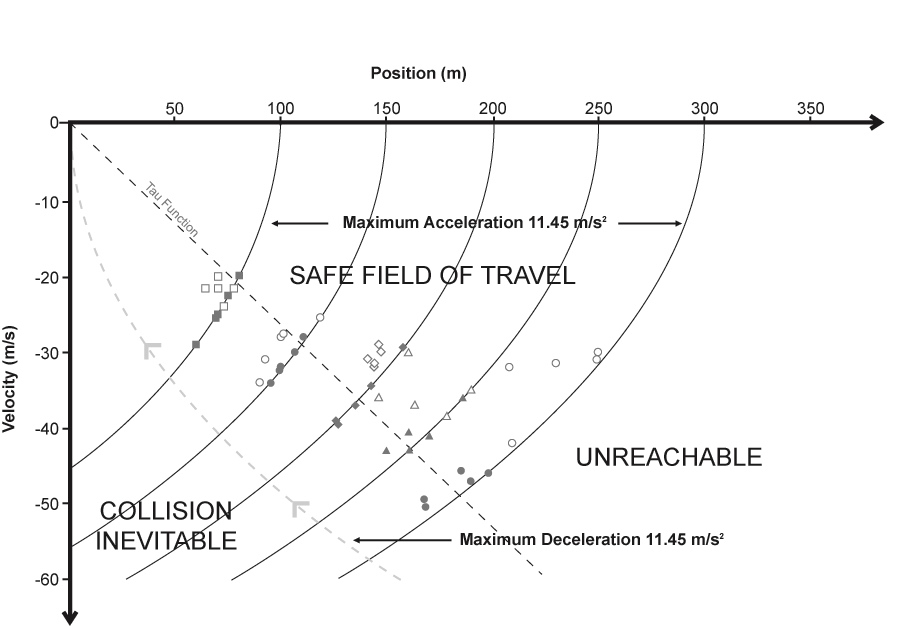

Early in my career, I was exposed to control theory due to working with Rich Jagacinski to model human tracking performance as a graduate student. Ever since, I see closed-loop systems everywhere I look. It seemed obvious to me that the language of control theory and the various representations (e.g., time histories, Bode plots of frequency response characteristics, state space diagrams) provided unique and valuable insights into nature. And I have bored countless students and colleagues to tears as I tried to explain the implications of gains and time delays for stability in closed-loop systems. The power of control theory led to an arrogant sense that I had a privileged view of nature! I sought out those who shared this perspective, and I expended a lot of energy to convince other social scientists that the language of control theory was essential for understanding human performance.

The mistake was not to believe that control theory is a valuable lens for exploring nature. The mistake was to think that it is the best or only path. My infatuation for control theory colored everything I looked at. Everything I observed, every paper I read, every debate or discussion with a colleague was filtered through the logic of control theory. I classified people with respect to whether they ‘got it’ or not! I tended to discount everything that I could not frame in the context of control theory. The problem was that I was so intent on preaching the ‘truth’ of control theory, that I stopped listening to other perspectives.

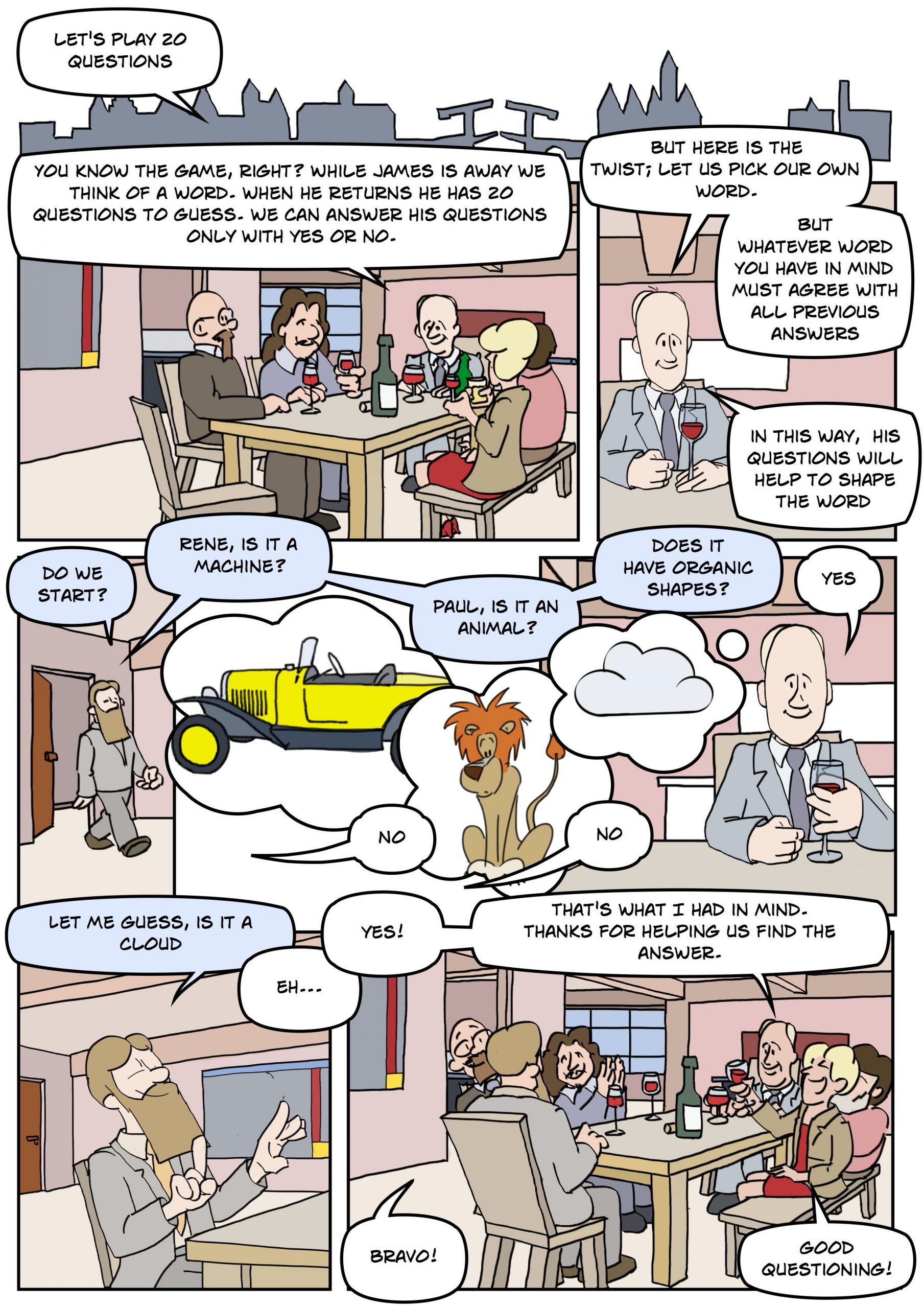

The deeper implication of Weinberg’s definition is captured in his principle that

“the things we see more frequently are more frequent: 1) because there is some physical reason to favor certain states; or 2) because there is some mental reason.”

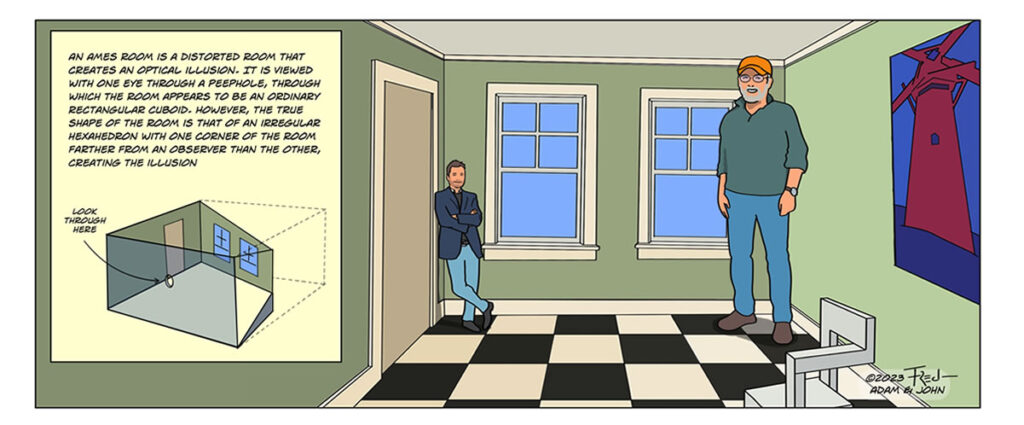

While I still believe that control theory captures some important aspects of nature, I now realize that the reason I see it everywhere, and the reason that I dismiss other perspectives is in part due to my own mental fixation. I now realize that it is impossible to separate these two possibilities from within control theory. You simply can’t tell whether your observations reflect natural constraints of the phenomenon or whether they reflect constraints of your perspective – if you only stand in one place. This is nicely illustrated by the Ames room illusion.

This is important because I am not the only victim. Over my career, I have watched others get locked into specific perspectives and have observed vicious debates as people defend one perspective against another. In an Either/Or world, there is a sense that only one perspective can be ‘true.’ So, if my perspective is right, yours must be wrong. I’ve watched constructivists war with ecological psychologists. I saw the development of nonlinear perspectives, and suddenly everything in nature was nonlinear – and all the insights from linear control theory were dismissed.

Gradually, I have come to understand that an important implication of the first principle of General Systems Thinking is:

To be humble.

Nature is incredibly complex relative to our sensemaking capabilities. Any representation or model that will makes sense to us, will only capture part of that complexity. Thus, every representation will be biased in some way. But also, many different perspectives can be valid in different ways. The challenge of General Systems Thinking is to be a better, more generous listener. Don’t let your skill with a particular perspective or a particular set of analytical tools blind you to the potential value of other perspectives. This is not simply about listening to other scientific perspectives. This is not simply about a debate between constructivists and ecologists, or between linear and nonlinear analytical tools. This is about listening to other forms of experience. Listening to the poets and artists. Listening to domain practitioners, listening to people from all levels of an organization.

In some sense General Systems Thinking is an attempt to find a balance between openness and skepticism. On the one hand, we need to be skeptical about all perspectives or models - including our own. On the other hand, we should be open to the potential values of different models and we need to be capable of using multiple models as we seek to distinguish the constraints that are intrinsic to the phenomenon of interest from the constraints of specific perspectives on that phenomenon. Our enthusiasm for the perspectives that we find to be most useful should be tempered by an appreciation of the potential of other perspectives and an openness to the insights that they offer. We need to move beyond the Either/Or debates to embrace a Both/And attitude of collaboration.

I can’t stop seeing closed-loop systems everywhere I look, and I will continue to share my passion for control theory with those who are interested, but I am working to temper my enthusiasm; to be a better listener; and to be a more generous colleague.

In sum, a system is a representation created by an observer; and General Systems Thinking is a warning against getting trapped by a narrow perspective on nature. It is a reminder that nature is far too complex to be fully captured within any single representation that we could create or that we could grasp. If you aren't boggled by the complexity of nature, you aren't looking carefully enough.