Successful innovation demands more than a good strategic plan; it requires creative improvisation. Much of the “serious play” that leads to breakthrough innovations is increasingly linked to experiments with models, prototypes, and simulations. As digital technology makes prototyping more cost-effective, serious play will soon lie at the heart of all innovation strategies, influencing how businesses define themselves and their markets.”

“Serious play turns out to be not an ideal but a core competence. Boosting the bandwidth for improvisation turns out to be an invitation to innovation. Treating prototypes as conversation pieces turns out to be the best way to discover what you yourself are really trying to accomplish.

Michael Schrage (1999)

“… generative design research [is] an approach to bring the people we serve through design directly into the design process in order to ensure that we can meet their needs and dreams for the future. Generative design research gives people a language with which they can imagine and express their ideas and dreams for future experience. The ideas and dreams can, in turn, inform and inspire stakeholders in the design and development process.

(Sanders & Stappers, 2012, p. 8)

The concept of "Design Thinking" is very much in vogue these days and I share the associated optimism that there is much that everyone can learn from engaging with the experiences of designers. However, my own experiences with design suggest that the label 'thinking' is misleading. For me the ultimate lesson from design experiences is the importance of coupling perception (analysis and evaluation) with action (creation of various artifacts). For me Schrage's concept of "Serious Play" and Sanders and Stapper's concept of "Co-Creation" provide more accurate descriptions of the power of design experiences for helping people to be more productive and innovative in solving complex problems. The key idea is that thinking does not happen in a disembodied head or brain, but rather, through physically and socially engaging with the world.

A number of years ago, I was part of a brief chat with Arthur Iberall (who designed one of the first suits for astronauts) and he was asked how he approached design? His response was: "I just build it. Then I throw it against the wall and build it again. Till eventually I can't see the wall. At that point I am beginning to get a good understanding of the problem."

The experience of building artifacts is where designers have an advantage on most of us. Building artifacts and interacting with the artifacts is an essential part of the learning and discovery process. Literally grasping and interacting with concrete objects and situations is a prerequisite for mentally grasping them. Trying to build and use something provides an essential test of assumptions and design hypotheses. In fact, I would argue that the process of creating artifacts can be a stronger test of an idea, than more classical experiments. The reason is that the same wrong assumptions that led to the idea to be tested are often also informing the design of the experiment to test the idea.

Thus, an important step in assessing an idea is to get it out of your head and into some kind of physical or social artifact (e.g, a storyboard, a persona, a wireframe, a scenario, an MVP, a simulation).

As a Cognitive Systems Engineer, I am strongly convinced of the value of Cognitve Work Analysis (CWA) as described by Kim Vicente (1999) and others (Naikar, 2013; Stanton, et al., 2018). However, although not necessarily intended by Kim or others, people often treat CWA as a prerequisite for design. That is, there is an implication that a thorough CWA must be completed prior to building any thing. However, I have found that it is impossible to do a thorough CWA without building things along the way. In my experience, it is best to think of CWA as a co-requisite with design in an iterative process, as illustrated in the Figure below.

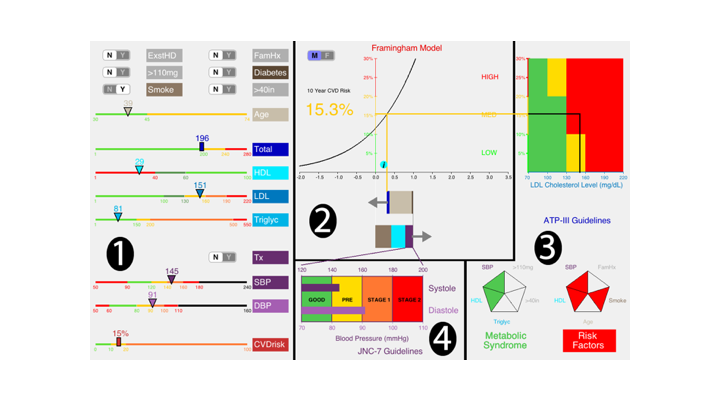

The figure illustrates my experiences with the development of the Cardiac Consultant App that is designed to help Family Practice Physicians to assess cardiovascular health. The first phase of this development was Tim McEwen's dissertation work at Wright State University. Tim and I did an extensive evaluation of the literature on cardiovascular health as part of our CWA. I particularly remember us trying to decompose the Framingham Risk equations. Discovering a graphical representation for the Cox Hazard function underlying this model was a key to our early representation concept. With Randy Green's help, we were able to code a Minimally Viable Product (MVP) that Tim could evaluate as part of his dissertation work. Note that MVP does not mean minimal functionality. Rather, the goal is to get sufficient functionality for empirical evaluation in a realistic context with MINIMAL developmental effort. The point of the MVP is to create an artifact for testing design assumptions and for learning about the problem.

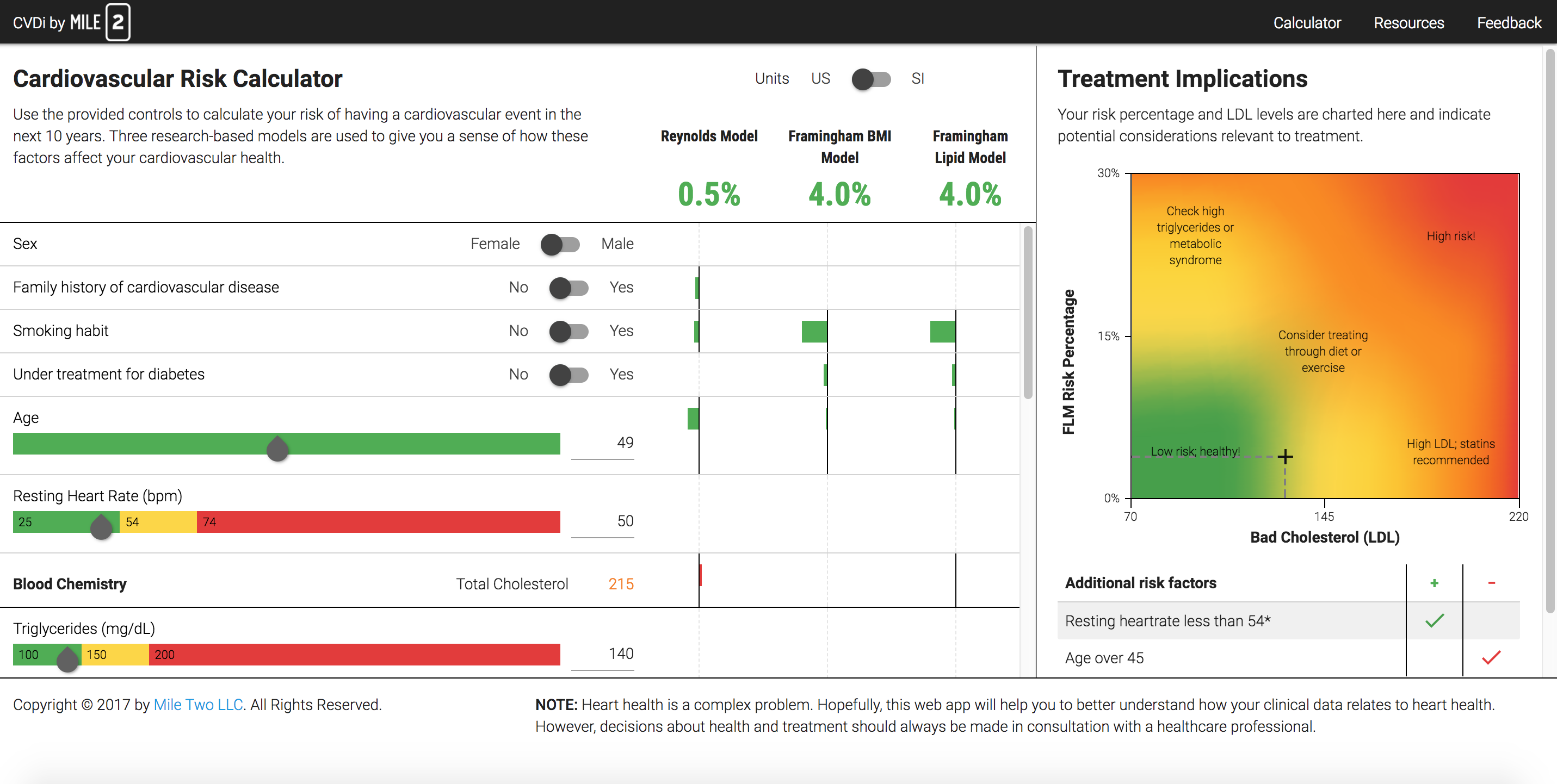

I was able to take the MVP that we generated in connection with Tim's dissertation to Mile Two, where the UX designers and developers were able to refine the MVP into a fully functioning web App (CVDi). I have to admit that I was quite surprised by how much the concept was improved through working with the UX designers at Mile Two. This involved completely abandoning the central graphic of the MVP, that had provided us with important insights into the Framingham model. We lost the graphic, but carried the insights forward and the new design allowed us to incorporate additional risk models into the representation (e.g., Reynolds Risk Model).

I was able to take the MVP that we generated in connection with Tim's dissertation to Mile Two, where the UX designers and developers were able to refine the MVP into a fully functioning web App (CVDi). I have to admit that I was quite surprised by how much the concept was improved through working with the UX designers at Mile Two. This involved completely abandoning the central graphic of the MVP, that had provided us with important insights into the Framingham model. We lost the graphic, but carried the insights forward and the new design allowed us to incorporate additional risk models into the representation (e.g., Reynolds Risk Model).

Despite the improvements, there was a major obstacle to implementing the design in a healthcare setting. The stand alone App required a physician to manually enter data from the patient's record (EHR system) into the App. This is where Asymmetric came into the picture. Asymmetric had extensive experience with the FIHR API and they offered to collaborate with Mile Two to link our interface directly to the EHR system - eliminating the need for physicians to manually enter data. In the course of building the FIHR backend, the UX group at Asymmetric offered suggestions for additional improvements to the interface representation, leading to the Cardiac Consultant. Again, I was pleasantly surprised by the value added by these changes.

So, the ultimate point of this story is to illustrate a Serious Play process that involves iteratively creating artifacts and then using the artifacts to elicit feedback in the analysis and discovery process. The artifacts are critical for pragmatically grounding assumptions and hypotheses. Further, the artifacts provide a concrete context for engaging a wide range of participants (e.g., domain experts and technologists) in the discovery process (participatory design).

I have found that it is impossible to do a thorough CWA without building things along the way. In my experience, it is best to think of CWA as a co-requisite with design in an iterative process, rather than a prerequisite.

At the end of the day, Design Thinking is more about doing (creating artifacts), than about 'thinking' in the conventional sense.

Works Cited

Naikar, N. 2013. Work Domain Analysis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Sanders, E.B. -N, Stappers, P.J. (2012). Convivial Toolbox. Amsterdam, BIS Publishers.

Schrage, M. (1999). Serious Play: How the World’s Best Companies Simulate to Innovate. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Stanton, N.A., Salmon, P.M., Walker, G.H. & Jenkins, D.P. (2018). Cognitive Work Analysis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Vicente, K.J. (1999). Cognitive Work Analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hi John. Nice post

Design is it self thinking, how the human mind solves for human need! User.... anything is design focused on a specific thing solving for a specific solution! It is a human-centric or user-centred approach to solving problems that commonly uses design based principles or practices

Great points! Thought provoking! Thinking IS serious play, isn't it? Sometimes it is also the most cost-effective method we have. Before we had digital prototyping tools, designers used paper, pencils, and (a lot of) mental visualization and manipulation (a.k.a., thinking?). I do see the value of testing our ideas in the real world and involving stakeholders as soon as possible, but I also see the risk of settling too early on whatever happens to be the dominant consensus of the day. Creativity sometimes requires visionary dissent and relentless pursuit of an "odd" idea. Should we all abandon the good old strategic planning and replace it with muddling through? I see them as complementary.

I guess I'm not sure what you mean by good old strategic planning - In my view this is a component of muddling through - we are constantly planning and acting on our plan and revising the plan as we get feedback from our actions. This can be happening at various time scales - depending on the availability of the feedback. For example, a football team may be developing a game plan during the week prior to the game (revising as a result of changes during the week - such as health of players). But many of the hypotheses will not be tested until game day -- and then plans are revised during the game as a result of what is observed during the play.