Early breakthroughs with respect to explaining mechanisms or inanimate things have shaped the narratives that have dominated early science. The scientific explanations of mechanisms were based on causal narratives with a strict ordering in time such that causes always precede effects. Thus, explaining an action (an effect or a response) involved tracing back along a metaphorical string of dominos until you found a satisfying explanation (i.e., the cause of the action). This resulted in a metaphorical string of dominos that is conveniently decomposable in time. That is, it is possible to isolate pairs of dominos, and it is possible to identify local and remote causes of an action. This led to experimental approaches that isolated pairs or small sequences of dominos to test specific hypotheses, with the promise that the understanding of these isolated parts (e.g., gears) could be combined to explain the entire sequence (e.g., behavior of the clock). In fact, there was an implication that it would ultimately be possible to explain the entire universe by isolating the first, primary domino and then tracing forward along the causal chain to predict the future.

It is not too surprising that early biologists and social researchers adopted this same narrative in their attempts to develop a scientific approach to explaining the actions of organisms. This is clearly illustrated by the stimulus response (SR) explanations of behavioral psychologists. Or the decomposition of cognition into an ordered series of discrete information processing stages. It is also why analogies to mechanisms – clockworks, servomechanisms, and computers were satisfying explanations for early social scientists.

However, it is becoming increasingly evident that the causal narrative that was successful for explaining the behavior of mechanisms will not lead to satisfying explanations for the behavior of organisms. In fact, there is growing suspicion that this causal narrative also falls short with respect to understanding complex physical systems (e.g., weather systems or dripping faucets). Thus, if the goal is to explain the behavior of organisms it becomes necessary to develop an alternative to the causal narrative.

Let’s consider some of the reasons why the causal narrative does not lead to a satisfying explanation for the behavior of organisms. First, the behavior of organisms is shaped by the potential consequences of actions. This is reflected in the fact that organisms pursue goals. This does not fit with the assumption that causes precede action. Thus, rather than stimuli causing actions, it could be argued that in many situations actions cause consequences which in turn lead to sensations and perceptions. The implication is that the coupling between stimuli and actions can be bi-directional or circular.

This circular coupling can be represented by adding feedback to the typical information processing model of cognition. Although early representations of information processing with feedback tended to preserve a fixed ordering in time consistent with a causal narrative in which sensing precedes perception, which precedes decision making, which precedes action. This is inconsistent with the circular dynamic that results from adding feedback.

In the circle there is no sense in which any stage necessarily precedes any other information processing stage. For example, Gibson observed that feet were a critical component of visual perception because movement is necessary to create the visual flow fields that specify our relations to the surfaces in our ecology. The figure below shows the conventional representation of information processing and an equivalent model that implies an alternative precedence between stages. The key point is that these representations are equivalent – illustrating that within the circle there is no fixed precedence in time between the stages of processing.

A second problem with the mechanistic narrative is that there is an implication that the transfer functions of the elements (e.g., the dominos or information processing stages) are fixed. This implies that pairs of dominos or stages of processing can be isolated and studied independently from the other dominos or stages, and that eventually the behavior of an organism could be explained by combining knowledge obtained by studying the independent elements. For example, it implies that decision making could be understood independently from sensing, perception, or action. However, research on Naturalistic Decision Making illustrates that decision making is not independent from recognition stages (e.g., selective attention and framing of the situation). And research on perception and action illustrates that a primary function of perception is to tune into the information that specifies the opportunities or constraints on action (i.e., the affordances).

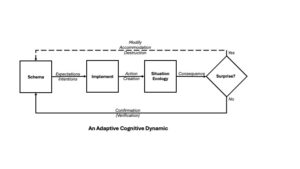

This was recognized by Piaget with respect to cognitive development and by Boyd with respect to the development of expertise. Piaget described two dynamics with respect to cognitive processes – assimilation and accommodation. The assimilation is reflected in the forward loop. This reflects how internal schemas (intentions and expectations) guide our interactions with the ecology. That is, the schema directs our attention and helps us to guess what actions will lead to satisfying interactions with our ecology. For Boyd this is analogous to creative action. If our guesses are correct, then the resulting feedback will confirm or reinforce the schema as a satisfying framing for productive action.

However, sometimes we will be surprised. That is the consequences will not be consistent with our expectations. The upper loop reflects what Piaget called accommodation and what Boyd called destruction. The feedback in this loop changes our schema (e.g., it adapts or destroys our old model to accommodate the unexpected consequences). That is, the transfer function for the box labeled schema is not fixed or stationary. The transfer function changes as a result of surprising consequences reflecting the capacity of organisms to adapt or learn from experience.

Thus, organisms are more complex than simple servomechanisms or computers with fixed transfer functions or programs specified by the engineer or programmer. They are engaged in a constant process of attunement to create a stable coupling with the ecology. In other words, the survival of the organism depends on them attuning to their ecology. A critical insight here is that stability is a constraint on the whole system (i.e., the coupling of organisms with their environment). This reverses the narrative with respect to parts and wholes. Rather than the whole being the sum of the parts, in a circular dynamic, the parts must satisfy the stability constraints on the whole. For example, if the ecology changes, the organism must also change in a way that maintains stability. Otherwise, the organism will become extinct. In other words, survival of the organism depends on maintaining a stable coupling with its ecology – the transfer function of the organism must adapt to the stability constraints of the coupling.

McRuer’s crossover model of how humans adapt to changing dynamics in a tracking task is a great illustration of how the transfer function of a human tracker must change to meet the demands of stability. If the transfer function of the plant is a simple gain (position control), then the human transfer function must have the properties of an integrator. But if the plant transfer function is an integrator (1st-order, velocity control), then the human transfer function must have the properties of a gain. The combined dynamic of human plus plant must meet the stability requirements of the entire loop (i.e., must be a low-pass filter).

You could also think about this in the context of competitive sports like tennis. To be consistently successful against different opponents it is necessary to adapt your style of play (your transfer function) in a way that counters the different strengths and weaknesses of your opponents.

Another aspect of the dynamic of circles that is inconsistent with the causal narrative is that the dynamics of circles cannot be dissected into a series of discrete instances in time (e.g., one domino or billiard ball hitting another in a series of discrete collisions). There is not a single signal in the information processing circle that then moves from one stage to the next. Rather, all stages are getting signals continuously. For example, you don’t have a sensation that becomes a perception that then drives a decision which then becomes an action. Rather, the organism is continuously sensing, which is continuously being integrated into on going perceptions, that inform on going decisions, that are integrated into ongoing actions. Further, the constraint on stability is not in time, it is over time. In other words, organisms are analog.

Finally, organisms are not processing single signals in one or two loops. Rather organisms are simultaneously dealing with a multitude of signals that are percolating through a multilayered network of multiple loops. This includes sensing through multiple modalities, perceiving multi-dimensional situations, and directing and coordinating the actions of multiple effectors. Thus, organisms are not reacting to discrete particles like colliding billiard balls. Rather, they are managing fields of information and coordinating fields of effectors. In motor control, this is reflected in the degrees of freedom problem – how to coordinate multiple muscles and joints to consistently achieve the same ends (e.g., an accurate throw to first base) under a wide range of different situations (e.g., reflecting different postures resulting from the need to first retrieve a ground ball).

The bottom line is that much of the biological and social sciences are framed within a causal narrative that was designed to explain inanimate mechanisms. However, it is becoming increasingly obvious to many researchers that this narrative does not lead to satisfying explanations for how organisms behave. Today a new narrative is being created based on the capacity of the organism to resiliently adapt to situated constraints. Rather than looking for causes, researchers are beginning to explore how behavior is shaped by constraints on perception and action. They are asking how patterns in fields of information (e.g., perceptual invariants) specify the opportunities and risks for action (e.g., affordances), relative to the successful pursuit of satisfying ends (e.g., healthy consequences, stable balance with the ecology, survival).

This is 😊 why your voice matters so much in this space we all share

Love how 🌻 you bring people together through your amazing creative work