In the early 1960s, we realized from analyses of industrial accidents the need for an integrated approach to the design of human-machine systems. However, we very rapidly encountered great difficulties in our efforts to bridge the gap between the methodology and concepts of control engineering and those from various branches of psychology. Because of its kinship to classical experimental psychology and its behavioristic claim for exclusive use of objective data representing overt activity, the traditional human factors field had very little to offer (Rasmussen, p. ix, 1986).

Cognitive Engineering, a term invented to reflect the enterprise I find myself engaged in: neither Cognitive Psychology, nor Cognitive Science, nor Human Factors. (Norman, p. 31, 1986).

The growth of computer applications has radically changed the nature of the man-machine interface. First, through increased automation, the nature of the human’s task has shifted from an emphasis on perceptual-motor skills to an emphasis on cognitive activities, e.g. problem solving and decision making…. Second, through the increasing sophistication of computer applications, the man-machine interface is gradually becoming the interaction of two cognitive systems. (Hollnagel & Woods, p. 340, 1999).

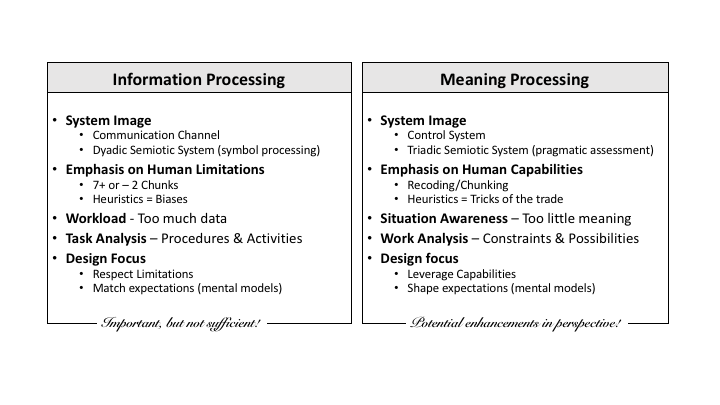

As reflected in the above quotes, through the 1980s and 90s there was a growing sense that the nature of human-machine systems was changing, and that this change was creating the demand for a new approach to analysis and design. This new approach was given the label of Cognitive Engineering (CE) or Cognitive Systems Engineering (CSE). Table 1, illustrates one way to characterize the changing role of the human factor in sociotechnical systems. As technologies became more powerful with respect to information processing capabilities, the role of the humans increasingly involved supervision and fault detection. Thus, there was increasing demand for humans to relate the activities of the automated processes to functional goals and values (i.e., pragmatic meaning) and to intervene when circumstances arose (e.g., faults or unexpected situations) such that the automated processes were no longer serving the design goals for the system. Under these unexpected circumstances, it was often necessary for the humans to create or invent new procedures on the fly, in order to avoid potential hazards or to take advantage of potential opportunities. This demand to relate activities to functional goals and values and to improvise new procedures required meaning processing.

In a following series of posts I will elaborate the differences between information processing and meaning processing as outlined in Table 1. However, before I get into the specific contrasts, it is important to emphasize that relative to early human factors, CSE is an evolutionary change, NOT a revolutionary change. That is, the concerns about information processing that motivated earlier human factors efforts were not wrong and they continue to be important with regards to design. The point of CSE is not that an information processing approach is wrong, but rather that it is insufficient.

The point of CSE is not that an information processing approach is wrong, but rather that it is insufficient.

The point of CSE is that design should not simply be about avoiding overloading the limited information capacities of humans, but it should also seek to leverage the unique meaning processing capabilities of humans. These meaning processing capabilities reflect peoples' ability to make sense of the world relative to their values and intentions, to adapt to surprises, and to improvise in order to take advantage of new opportunities or to avoid new threats. In following posts I will make the case that the overall vision of a meaning processing approach is more expansive than an information processing approach. This broader context will sometimes change the significance of specific information limitations. It will also provide a wider range of options for by-passing these limitations and for innovating to improve the range and quality of performance of sociotechnical systems.

In other words, I will argue for a systems perspective - where the information processing limitations must be interpreted in light of the larger meaning processing context. I will argue that constructs such as 'expertise' can only be fully understood in terms of qualities that emerge at the level of meaning processing.

Hollnagel, E. & Woods, D.D. (1999). Cognitive Systems Engineering: New wine in new bottles. In. J. Human-Computer Studies, 51, 339-356.

Norman, D.A. (1986). Cognitve Engineering. In D.A. Norman & S.W. Draper (Eds). User-Centered System Design, 31-61, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rasmussen, J. (1986). Information Processing and Human-Machine Interaction: An Approach to Cognitive Engineering. New York: North Holland.