Symbols help us make tangible that which is intangible. And the only reason symbols have meaning is because we infuse them with meaning. That meaning lives in our minds, not in the item itself. Only when the purpose, cause or belief is clear can the symbol command great power (Sinek, 2009, p. 160)

As this quote from Sinek suggests, symbols (e.g., alphabets, flags, icons) are created by humans. Thus, the 'meaning' of the symbols will typically reflect the intentions or purposes motivating their creation. For example, as a symbol, a country's flag might represent the abstract principles on which the country is founded (e.g., liberty and freedom for all). However, it would be a mistake to conclude from this (as many cognitive scientists have) that all 'meaning' lives in our minds. While symbols may be a creation of humans - meaning is NOT.

Let me state this again for emphasis:

Meaning is NOT a product of mind!

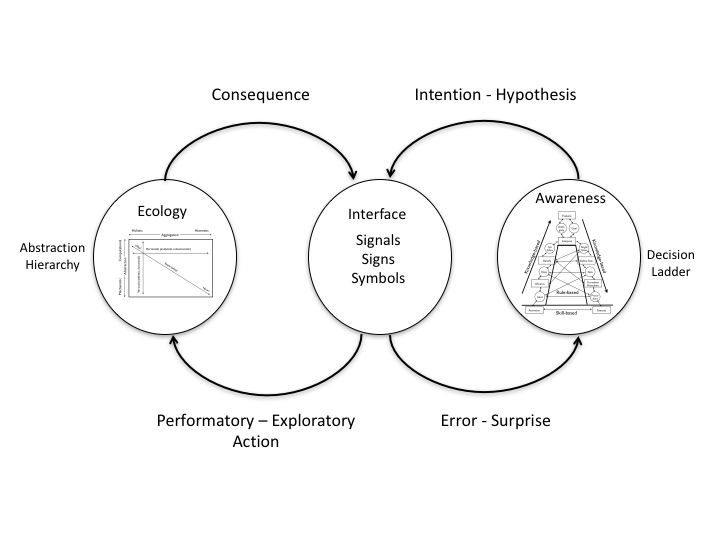

As the triadic model of a semiotic system illustrated in the figure below emphasizes meaning emerges from the functional coupling between agents and situations. Further, as Rasmussen (1986) has emphasized this coupling involves not only symbols, but also signs and signals.

Signs (as used by Rasmussen) are different than 'symbols' in that they are grounded in social conventions. So, the choice of a color to represent safe or dangerous, or of an icon to represent 'save' or 'delete' has its origins in the head of a designer. At some point, someone chose 'red' to represent 'danger,' or chose a 'floppy disk' image to represent save. However, over time this 'choice' of the designer can become established as a social convention. At that point, the meaning of the the color or the icon is no longer arbitrary. It is no longer in the head of the individual observer. It has a grounding in the social world - it is established as a social convention or as a cultural expectation. People outside the culture may not 'pick-up' the correct meaning, but the meaning is not arbitrary.

Rasmussen used the term sign to differentiate this role in a semiotic system from that of 'symbols' whose meaning is open to interpretation by an observer. The meaning of a sign is not in the head of an observer, for a sign the meaning has been established by a priori rules (social or cultural conventions).

for a sign the meaning has been established by a priori rules (social or cultural conventions)

Signals (as used by Rasmussen) are different than both 'symbols' and 'signs' in that they are directly grounded in the perception-action coupling with the world. So, the information bases for braking your automobile to avoid a potential collision, or for catching a fly ball, or for piloting an aircraft to a safe touchdown on a runway are NOT in our minds! For example, structures in optical flow fields (e.g., angle, angular rate, tau, horizon ratio) provide the state information that allows people to skillfully move through the environment. The optical flow field and the objects and events specified by the invariant structures are NOT in the mind of the observer. These relations are available to all animals with eyes and can be leveraged in automatic control systems with optical sensors. These signals are every bit as meaningful as any symbol or sign yet these are not human inventions. Humans and other animals can discover the meanings of these relations through interaction with the world, and they can utilize these meanings to achieve satisfying interactions with the world (e.g. avoiding collisions, catching balls, landing aircraft), but the human does not 'create' the meaning in these cases.

for a signal the meaning emerges naturally from the coupling of perception and action in a triadic semiotic system. It is not an invention of the mind, but it can be discovered by a mind.

In the field of cognitive science debates have often been cast in terms of whether humans are 'symbol processors,' such that meaning is constructed through mental computations, or whether humans are capable of 'direct perception,' such that meaning is 'picked-up' through interaction with the ecology. One side places meaning exclusively in the mind, ignoring or at least minimizing the role of structure in the ecology. The other side places meaning in the ecology, minimizing the creative computational powers of mind.

This framing of the question in either/or terms has proven to be an obstacle to progress in cognitive science. Recognizing that the perception-action loop can be closed through symbols, signs, and signals opens the path to a both/and approach with the promise of a deeper understanding of human cognition.

Recognizing that the perception-action loop can be closed through symbols, signs, and signals opens the path to a both/and approach with the promise of a deeper understanding of human cognition.

Thanks John,

I have been trying to figure out how to use these three terms correctly. I've a slightly different background, and wondering if you'd like to comment (by email or in an edit) about Ferdinand de Saussure's "arbitrariness of the sign". I think what you say here fits with my interpretation of de Saussure, but you may not think so.

p

This is needlessly complex. Much simpler language could be used if the goal is to create understanding. The more abstractions you use in explaining other abstractions, the less understanding you will create. Take the sentence "As the triadic model of a semiotic system illustrated in the figure below emphasizes meaning emerges from the functional coupling between agents and situations." Is triadic model of a semiotic system"necessary to understanding; and can "functional coupling between agents and situations" be said more clearly?" And the illustration is far from self-explanatory. It seems to me that the social sciences often (in academia) often use needlessly complex language (high-level abstractions) in order to sound more scientific, but what they need it to discover theories that actually lead to real-world results outside of academia. I think many in the general discipline of psychology understand that this might never happen, which is why, I surmise, neuropsychology is a rapidly growing field. I don't like to see this. I will give my email below (as required), but I expect it to be confidential.

Yes, this is a fair criticism. I do presume that the reader has some familiarity with background work in cognition and semiotics. But we do try to apply this literature in our work to design decision support systems, where we do our best to develop interfaces that are intuitive and easy to understand by people in specific domains. But this post is intended for other academics who are engaged in conversations related to the nature of cognitive systems. These conversations have a history and I understand that this might seem "needlessly complex' to someone who does not know that history.

Wonderful piece.