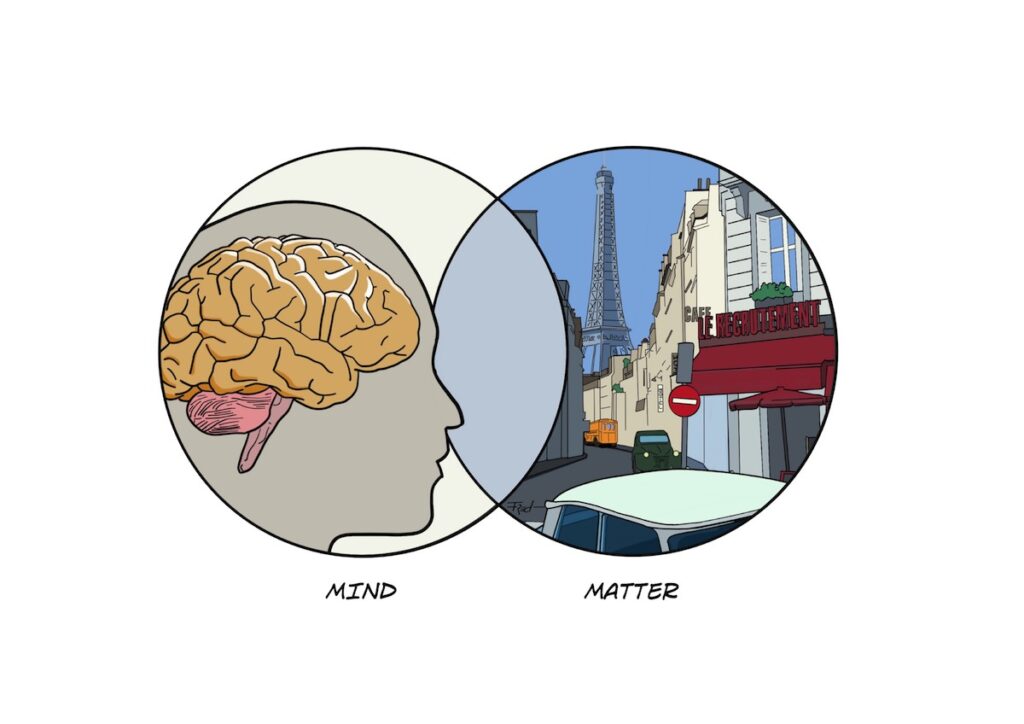

Conventionally, the question, “What is reality?” is framed as an EITHER/OR proposition that is illustrated as a Venn diagram. Within this framework, the options seem to be - to either accept one of the circles as real, and the other as an illusion, or to accept both circles as two different, distinct realities.

Accepting mind as the single reality is called mentalism. While this is generally presented as a logical possibility, few people give serious consideration to this possibility. In essence, this suggests that we are all living in the Matrix – that there is no matter – it is purely a construction of our minds.

Accepting matter as the single reality is called materialism. This position is embraced by many people. The implication of this position is that the mind is a by-product of matter and that the experiences that we attribute to mind are nothing more than the results of chemical and biological processes in brains.

The final option, that tends to dominate Western culture is that there are two distinct realities. On the one hand, there is the objective world of matter – that is the domain of the physical and biological sciences. And on the other hand, there is the subjective world of mind – that is the domain of the social sciences and religion. This is called dualism, and in contrast to materialism, dualism contends that there are real aspects of our mental and spiritual lives that cannot be completely reduced to chemical and biological brain processes.

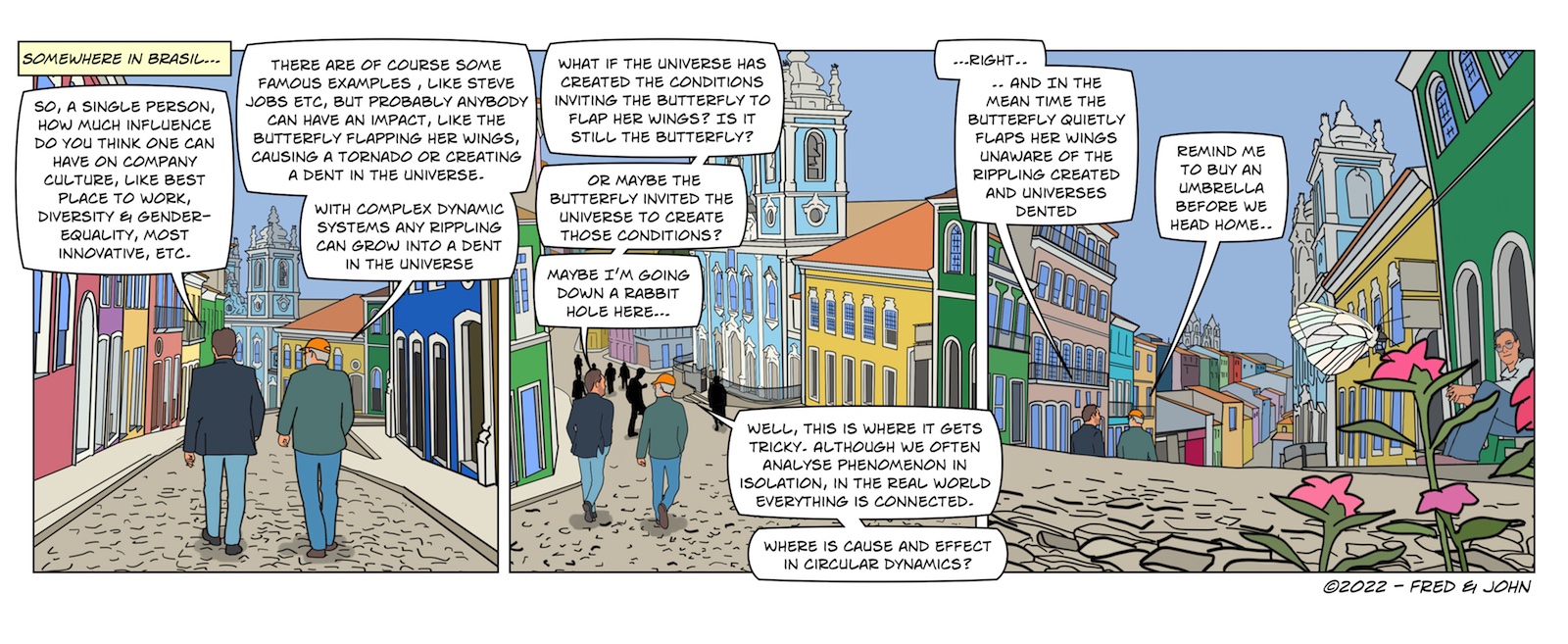

Dualism, however, raises another puzzle. If mind and matter are two distinct realities, how is it possible for them to interact? How is it possible for a mind to know the world of matter?

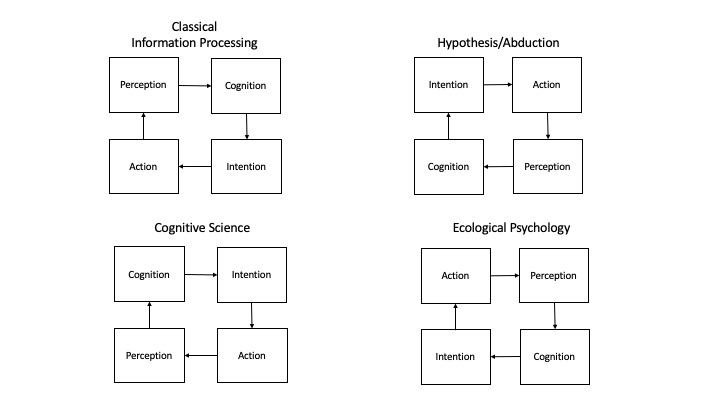

A large body of research suggests that the mind has great difficulty in coming to know the world of matter as it is. The research on human perception and cognition suggests that the mind is prone to illusions and biases. Conventional wisdom suggests that we construct mental models of the actual world using partial, noisy data from our senses. For example, we must construct a model of 3-dimensional space from two distorted, upside-down, 2-dimensional retinal images, augmented by our tactile senses.

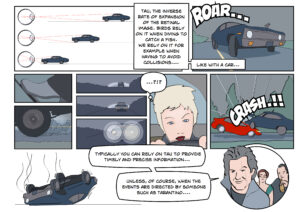

It's not surprising that our experiences don’t always correspond with the world of objective reality associated with the ticks of a clock or the ticks on a ruler. Actually, the surprising thing is that sometimes people are able to interact with the world quite skillfully – to run through the forest over rough terrain without colliding with a tree; to drive at highway speeds in dense traffic without colliding with another car; to pitch a baseball accurately, to hit it, and to catch a fly ball; to intercept and volley a soccer ball past a goalie; to fly and land an aircraft safely.