Why Wundt?

The development of psychology as a science has tended to buy into and to reinforce the dichotomy of mind and matter. In most histories of psychology, Wilhelm Wundt's lab is identified as the first experimental psychology lab - as the birthplace of a scientific psychology. However, certainly there were others who had experimental programs before Wundt (e.g., Fechner and Helmholtz).

Perhaps the reason is that whereas Fechner and Helmholtz were studying relations between mind and matter (i.e., psychophysics), Wundt, with the emphasis on introspection, framed psychology as mental chemistry. This methodology emphasized the distinction between the stimulus as an object in the ecology and the stimulus as a property of mind. And there was a clear understanding that it was only the properties of mind that were of interest to the 'science' of psychology. In fact, Titchener would characterize associations between introspections and the ecological object as 'stimulus errors.' And Ebbinghaus would focus on nonsense syllables in an attempt to isolate the mental chemistry of memory from experiences outside the experimental context.

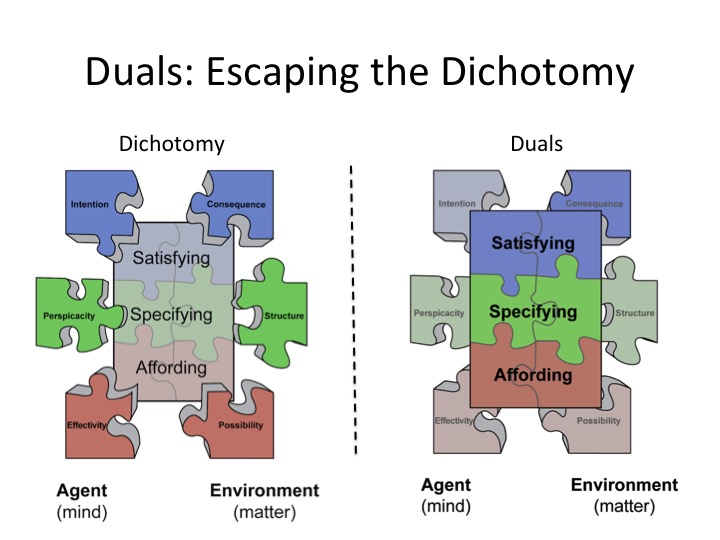

Of course, not everyone bought into this. William James characterized the experimental work of Wundt and Titchener as 'brass instrument psychology.' In framing a functionalist psychology, James was particularly interested in mind as a capacity for adaptation in relation to the dynamics of natural selection. In this context, the pragmatic relations between mind and matter (satisfying the demands of survival) were a central concern.

Note that Wundt's research program was very broad, particularly if you consider his Volkerpsychologie. Thus, the key point is not to criticize his choice of focus or specialization. Rather, it is the later field of psychology that choses this focus as the 'birthplace' of the science that reinforces the idea that the science of psychology should be framed exclusively in terms of the mind, in isolation from matter (e.g., a physical ecology).

While Behaviorism brought the methodology of introspection under suspicion, and shifted attention to 'behavior,' the idea of 'stimulus' remained psychological (if not mentalistic) in that the nature of the stimulus (e.g., reinforcement versus punishment) was derived from the impact on behavior (e.g., increasing or reducing its likelihood), rather than as a consequence of its physical attributes. Thus, the Laws of learning could be pursued independently from any physical principles (e.g., the Laws of Motion).

The Computer Metaphor and Symbol Processing

With the development of information technologies, the mind again became a legitimate object of study. However, now the topic was not mental chemistry, but mental computation. The computer metaphor added new legitimacy to the separation of mind (i.e., software) from matter (i.e., hardware). And the new science of linguistics, with its basis in a dyadic model of semiotics (Saussure) shifted the focus to symbol processing in a way that made the link between the symbol and the ecology completely arbitrary. The focus was on the internal computations - the rules of grammar, the 'interpretation' that resulted from the mental computations. It became apparent to many that the stimuli for mental computations were arbitrary signs (e.g. C-A-T) and that the 'meanings' of these arbitrary signs were constructed through mental computations.

In this climate, people such as James Gibson, who followed the Functionalist traditions of William James in pursuing the significance of mind for adapting to an ecology, were marginalized. The field of psychology became the study of internal computational mechanisms for processing arbitrary signs. The focus of psychology was to identify the internal constraints of the computational mechanisms. In this context, the most interesting phenomena were errors, illusions, and biases, because these might give hints to the internal constraints of the computations. A mind that was successful or situations where people behaved skillfully tended to be ignored - because the internal constraints were not salient when the mind worked well.

Neuroscience

Ironically, in linking mental computations to brain structures, the dichotomy between mind and matter continues to be reinforced, at least to the extent that 'matter' reflects the physical constraints in an ecology. While neuroscience involves the admission that the hardware matters, by isolating the computation to the 'brain' there remains a strong tendency for psychology to ignore the role of other physical properties of the body and ecology in shaping human experience. For many, neuroscience effectively reduces psychology and cognition back to a mental chemistry or to brain mechanisms that can be understood independently from the pragmatic aspects of experience in a complex ecology. In this regard, I fear that increased enthusiasm for neuroscience is a backward step or an obstacle to progress toward a science of human experience.