Introduction

It has long been recognized that in complex work domains such as management and healthcare, the decision-making behavior of experts often deviates from the prescriptions of analytic or normative logic. The observed behaviors have been characterized as intuitive, muddling through, fuzzy, heuristic, situated, or recognition-primed. While there is broad consensus on what people typically do when faced with complex problems, the interesting debate, relative to training decision-making or facilitating the development of expertise, is not about what people do, but rather about what people ought to do.

On the one hand, many have suggested that training should focus on increasing conformity with the normative prescriptions. Thus, the training should be designed to alert people to the generic biases that have been identified (e.g., representativeness heuristic, availability heuristic, overconfidence, confirmatory bias, illusory correlation), to warn people about the potential dangers (i.e., errors) associated with these biases, and to increase knowledge and appreciation of the analytical norms. In short, the focus of training clinical decision making should be on reducing (opportunities for) errors in the form of deviations from logical rationality.

On the other hand, we (and others) have suggested that the heuristics and intuitions of experts actually reflect smart adaptations to the complexities of specific work domains. This reflects the view that heuristics take advantage of domain constraints leading to efficient ways to manage the complexities of complex (ill-structured) problems, such as those in healthcare. As Eva & Norman [2005] suggest, “successful heuristics should be embraced rather than overcome” (p. 871). Thus, to support clinical decision making, training should not focus on circumventing the use of heuristics but should focus on increasing the perspicacity of heuristic decision making, that is, on tuning the (recognition) processes that underlie the adaptive selection and use of heuristics in the domain of interest.

Common versus Worst Things in the ED

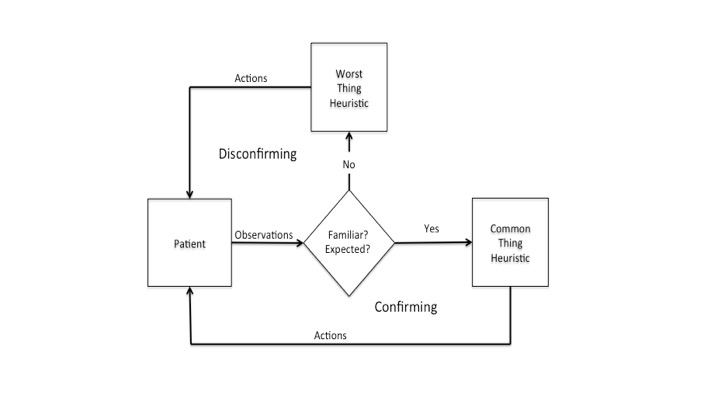

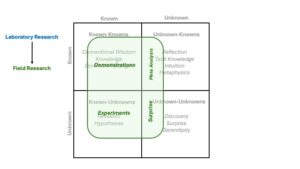

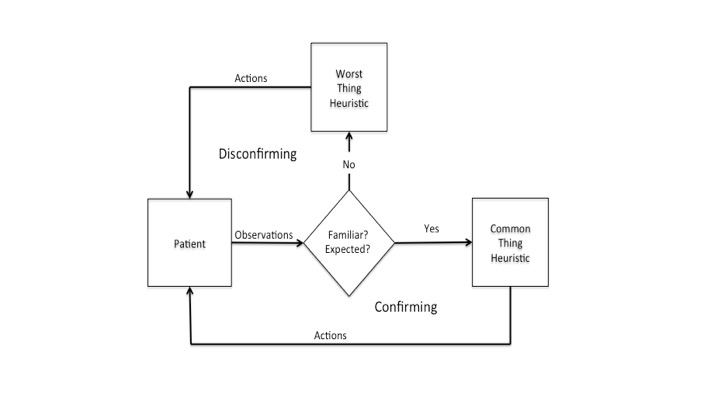

In his field study of decision-making in the ED, Feufel [2009] observed that the choices of physicians were shaped by two heuristics: 1) Common things are common; and 2) Worst case. Figure 1 illustrates these two heuristics as two-loops in an adaptive control system. The Common Thing heuristic aligns well with classical Bayesian norms for evaluating the state of the world. It suggests that the hypotheses guiding treatment should reflect a judgment about what is most likely based on the prior odds and the current observations (i.e., what is most common given the symptoms). Note that this heuristic biases physicians toward a ‘confirmatory’ search process, as their observations are guided by beliefs about what might be the common thing. Thus, tests and interventions tend to be directed toward confirming and treating the common thing.

Figure 1. Illustrates the decision-making process as an adaptive control system guided by two complementary heuristics: Common Thing and Worst Thing.

Figure 1. Illustrates the decision-making process as an adaptive control system guided by two complementary heuristics: Common Thing and Worst Thing.

The Worst Case heuristic shifts the focus from ‘likelihood’ to the potential consequences associated with different conditions. Goldberg, Kuhn, Andrew and Thomas [2002] begin their article on “Coping with Medical Mistakes” with the following example:

“While moonlighting in an emergency room, a resident physician evaluated a 35-year-old woman who was 6 months pregnant and complaining of a headache. The physician diagnosed a ‘mixed-tension sinus headache.’ The patient returned to the ER 3 days later with an intracerebral bleed, presumably related to eclampsia, and died (p. 289)”

This illustrates an ED physician’s worst nightmare – that a condition that ultimately leads to serious harm to a patient will be overlooked. The Worst Case heuristic is designed to help guard against this type of error. While considering the common thing, ED physicians are also trained to simultaneously be alert to and to rule-out potential conditions that might lead to serious consequences (i.e., worst cases). Note that the Worst Case heuristic biases physicians toward a disconfirming search strategy as they attempt to rule-out a possible worst thing – often while simultaneously treating the more likely common thing. While either heuristic alone reflects a bounded rationality, the coupling of the two as illustrated in Figure 1 tends to result in a rationality that can be very well tuned to the demands of emergency medicine.

Ill-defined Problems

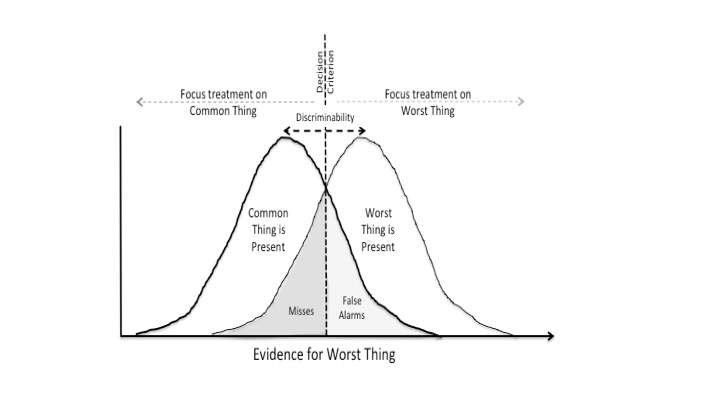

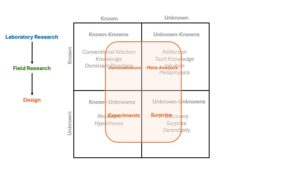

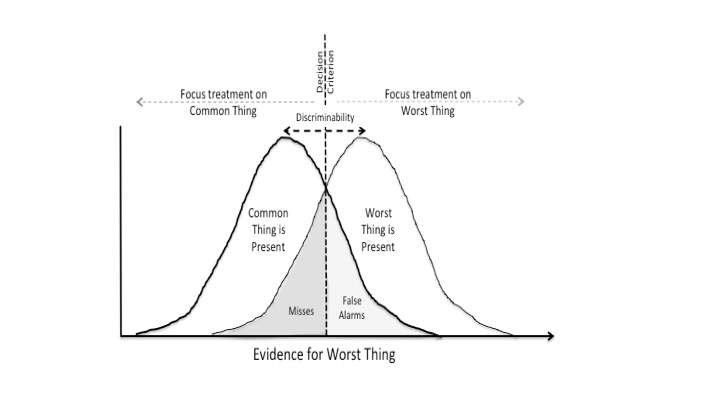

In contrast to the logical puzzles that have typically been used in laboratory research on human decision-making, the problems faced by ED physicians are ‘ill-defined’ or ‘messy.’ Lopes [1982] suggested that the normative logic (e.g., deduction and induction logic) that works for comparatively simple logical puzzles will not work for the kinds of ill-defined problems faced by ED physicians. She suggests that ill-defined problems are essentially problems of pulling out the ‘signal’ (i.e., the patient’s actual condition) from a noisy background (i.e., all the potential conditions that a patient might have). Thus, the theory of signal detection (or observer theory) illustrated in Figures 2 & 3 provides a more appropriate context for evaluating performance.

Figure 2. The logic of signal detection theory is used to illustrate the challenge of discriminating a worst case from a common thing.

Figure 2. The logic of signal detection theory is used to illustrate the challenge of discriminating a worst case from a common thing.

Figure 2 uses a signal detection metaphor to illustrate the potential ambiguities associated with discriminating the Worst Cases from the Common Things in the form of two overlapping distributions of signals. The degree of overlap between the distributions represents the potential similarity between the symptoms associated with the alternatives. The more overlap, the harder it will be to discriminate between potential conditions. The key parameter with respect to clinical judgment is the line labeled Decision Criterion. The placement of this line reflects the criterion that is used to decide whether to focus treatment on the common thing (moving the criteria to the right to reduce false alarms) or the worst thing (moving the criteria to the left to reduce misses). Note that there is no possibility for perfect (i.e., error free) performance. Rather, the decision criterion will determine the trade-off between two types of errors: 1) false alarms – expending resources to rule out the worst case, when the patient’s condition is consistent with the common thing; or 2) misses – treating the common thing, when the worst case is present.

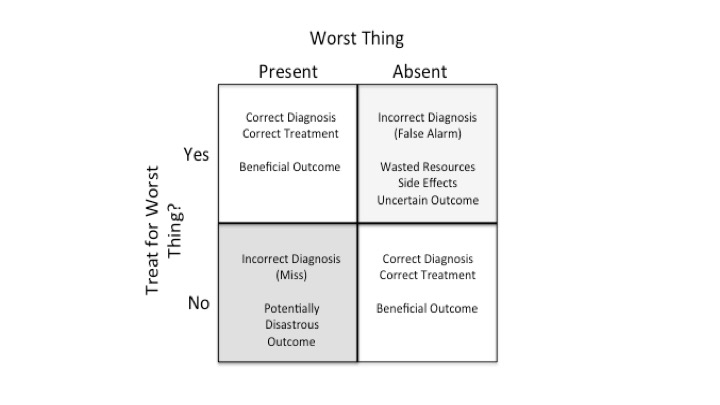

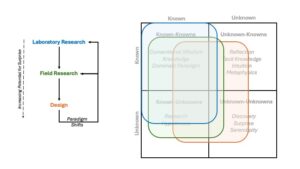

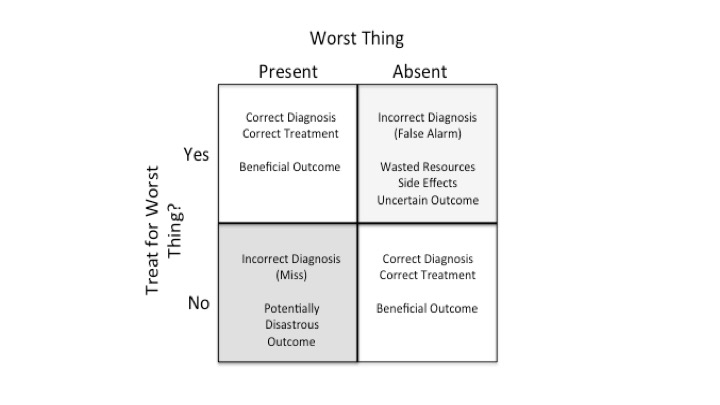

In order to address the question of what is the ‘ideal’ or at least ‘satisfactory’ criterion for discriminating between treating the common thing or the worst thing it is necessary to consider the potential values associated with the treatments and potential consequences as illustrated in the pay-off matrix in Figure 3. Thus, the decision is not simply a function of finding ‘truth.’ Rather, the decision involves a consideration of values: What costs are associated with the tests that would be required to conclusively rule-out a worst case? How severe would be the health consequences of missing a potential worst case? Missing some things can have far more drastic consequences than missing other things.

Figure 3. The payoff matrix is used to illustrate the values associated with potential errors (i.e., consequences of misses and false alarms).

Figure 3. The payoff matrix is used to illustrate the values associated with potential errors (i.e., consequences of misses and false alarms).

The key implication of Figures 2 and 3 is that eliminating all errors is not possible. Given enough time, every ED physician will experience both misses and false alarms. That is, there will be cases where they miss a worst case and other cases where they pursue a worst case only to discover that it was the common thing. While perfect performance (zero-error) is an unattainable goal, the number of errors can be reduced by increasing the ability to discriminate between potential patient states (e.g., recognizing the patterns, choosing the tests that are most diagnostic). This would effectively reduce the overlap between the distributions in Figure 2. The long-range or overall consequences of any remaining errors can be reduced by setting the decision criterion to reflect the value trade-offs illustrated in Figure 3. In cases where expensive tests are necessary to conclusively rule-out potential worst cases, this raises difficult ethical questions involving weighing the cost of missing a worst case, versus the expense of the additional tests that in many cases will prove unnecessary.

Conclusion

The problems faced by ED physicians are better characterized in terms of the theory of signal detection, rather than in terms of more classical models of logic that fail to take into account the perceptual dynamics of selecting and interpreting information. In this context, heuristics that are tuned to the particulars of a domain (such as common things and worst cases) are intelligent adaptations to the situation dynamics (rather than compromises resulting from internal information processing limitations). While each of these heuristics is bounded with respect to rationality, the combination tends to provide a very intelligent response to the situation dynamics of the ED. The quality of this adaptation will ultimately depend on how well these heuristics are tuned to the value system (payoff matrix) for a specific context.

Note that while the signal detection theory is typically applied to single discrete observations, the ED is a dynamic situation as illustrated in Figure 1, where multiple samples are collected over time. Thus, a more appropriate model is Observer Theory, which extends the logic of signal detection to dynamic situations, where judgment can be adjusted as a function of multiple observations relevant to competing hypotheses [see Flach and Voorhorst, 2016; or Jagacinski & Flach, 2003 for discussion of Observer Theory]. However, the implication is the same - skilled muddling involves weighing evidence in order to pull the 'signal' out from a complex, 'noisy' situation.

Finally, it is important to appreciate that with respect to the two heuristics, it is not a case of 'either-or,' rather it is a 'both-and' proposition. That is the heuristics are typically operating concurrently - with the physician often treating the common thing, while awaiting test results to rule out a possible worst case. The challenge is in allocating resources to the concurrent heuristics, while taking into account the associated costs and benefits as reflected in a value system (payoff matrix).

Figure 1. Illustrates the decision-making process as an adaptive control system guided by two complementary heuristics: Common Thing and Worst Thing.

Figure 1. Illustrates the decision-making process as an adaptive control system guided by two complementary heuristics: Common Thing and Worst Thing. Figure 2. The logic of signal detection theory is used to illustrate the challenge of discriminating a worst case from a common thing.

Figure 2. The logic of signal detection theory is used to illustrate the challenge of discriminating a worst case from a common thing. Figure 3. The payoff matrix is used to illustrate the values associated with potential errors (i.e., consequences of misses and false alarms).

Figure 3. The payoff matrix is used to illustrate the values associated with potential errors (i.e., consequences of misses and false alarms).