Is there such a thing as an 'objective truth' that is independent of an individual's experience? For many, the point of science is to discover such a truth that is invariant across observers. On the other hand, one might ask whether the unique subjective experiences of individuals are valid?

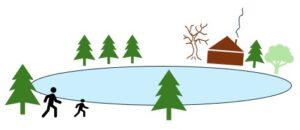

Consider the question of whether a frozen pond will support an individual. We can 'objectively' measure the thickness of the ice. We can do experiments to objectively determine what weight the ice will support. But we can't say 'objectively' whether the ice will afford walking, because the experience of 'support' depends both on the thickness of the ice and the weight of an individual. The same frozen pond can mean different things to different individuals. So, the affordance of support or the functional meaning of the ice cannot be specified independently from an observer's weight.

Thus, individuals of different weights might experience the frozen pond differently. The lighter individual might validly see the pond as a safe field of travel, and the heavier individual might validly see the pond as an unsafe field of travel. The subjective experiences are different, but both might be valid.

On the other hand, the experience for both individuals might be ambiguous. The lighter individual might experience the pond as potentially dangerous, and decide to walk around the pond, rather than take a more direct path across the pond. Or the heavier individual might perceive the pond as a safe path, but then discover his error when the ice cracks and he falls through.

If the pair walks together, the lighter individual might convince the heavier individual that the pond is safe (which it is for her) and they might then both walk together across the ice, and both fall into the lake when the ice fails to support their combined weight.

Thus, different experiences might be valid - though different. And common experiences/interpretations might be valid for one individual, but not for another or not for the group - though the interpretations are identical.

Note in an attempt to achieve objectivity, science establishes measures/rulers like pounds and inches that are observer independent. But these measures are not invariantly related to peoples' experiences. Do people experience the world relative to these observer independent metrics/standards? Or do people experience the world pragmatically? Does a surface support locomotion? Is a gap pass-through-able? Is an object reachable or graspable? We don't directly experience the world in pounds or inches. Rather we experience the world directly in functional terms - we directly experience what the world affords. The measures of the physicist are abstractions - not direct experiences!

The observer independent metrics serve the physical sciences well, but are they appropriate for the social sciences? Does it make sense to gauge whether people's experiences or perceptions are 'right' or 'wrong' using the metrics of the physical sciences? This is the question that James Gibson asked? And he concluded that perception is not based in "the world of physics, but the world at the level of ecology." Similarly, Jacob Johann von Uexkull introduced the construct of 'umwelt' to illustrate how functional ecologies can be describe in relation to the unique capabilities of different animals.

The implication of this is that the truth, validity or meaning of our experiences is not observer independent. Yet, they also are not arbitrary. The fact of whether the frozen pond will support us is a pragmatic truth, and the ultimate proof is in the doing. The ultimate tests of our perceptions (i.e., the meanings that are most significant) are the potential consequences of our actions!